America has an addiction to punishment.

Posted on 17 June 2016

And it’s failing us.

by Matt Haney

Whether in our schools or the justice system, our instinct has often been to punish first, ask questions later.

It is time that we as individuals, as a community, and as country stop giving punishment a free pass.

When I started as a School Board Member in San Francisco a few years back I asked around for our evidence that out-of-school suspensions were effective.

As a school district, we were suspending thousands of children from school every year, disproportionately students of color, leading to countless hours of missed class time, we must have a good reason for it, right?

People literally laughed in my face.

Evidence that suspensions work?

Why would we have that?

Ridiculous question.

Rookie.

There’s no answer because all the actual evidence tells us the exact opposite.

Suspensions make children more likely to misbehave and be suspended again, drop out, and end up in the criminal justice system. Not only do suspensions not change behavior positively, they actually make things much worse.

But that’s exactly how punishment often works within our society. Punishment doesn’t need to justify itself. It is its own justification.

Why do we punish students with suspensions when they misbehave? Because we punish students with suspensions when they misbehave.

That’s just what we do. No further explanation needed.

Instead of the burden being placed on punishment, we allow punishment to place the burden on us: We force ourselves to search for reasons as to why we shouldn’t harm someone when they do something we don’t like.

The assumption is always that we must hurt them.

But hurting doesn’t always help. In fact, it often makes things worse.

For that reason, you would imagine that we would place the highest burden on punishment to justify itself to us.

Hurting someone is serious business, and should always come with high standards for us to meet.

But we’ve got it backwards: We’ve created a world where we have to justify ourselves to punishment; and it’s a high bar. Usually too high.

Our justice system is the worst culprit of this dizzying circular logic that always leads us to more punishment.

Because we lock people up for long periods of time when they do something we don’t like.

Any evidence that long sentences, particularly for drug offenses or nonviolent crimes, serve as a deterrent?

None.

Any evidence that serving a long prison sentence will make a person less likely to re-offend?

None.

In fact, all the evidence that we have, just like with school suspensions, points to the opposite.

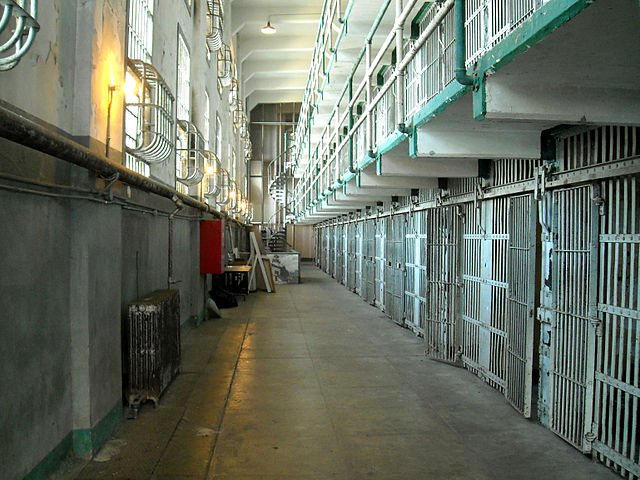

Putting people in crowded cells disconnected from their families and society, without treatment for their underlying problems, surrounded by others who have been convicted of crimes, and then continuing to punish them by labeling them as a felon for the rest of their life, actually makes it more likely that people re-offend.

Who knew?

Of course, not everyone who does something “bad” is punished. Punishment is wielded most harshly for the marginalized, powerless, and demonized in our society. For people of color, and especially children of color, guilt is more often presumed, so punishment is quicker, more brutal, and less forgiving.

So when rich white kids have a problem with drugs, they are called “troubled,” viewed as having an underlying need to be addressed, and are sent to rehab. And often that approach works, with these “troubled” kids heading off to college and on to high paying jobs.

But when black children do similar things, they are demonized as bad kids, apparently only capable of responding to punishment, and are put in a cell. That time in a cell leads to more time in a cell, and so on and so on, eventually punishment becomes the justification for more punishment.

And punishment is not always so intentional and conscious. It can also be found in the economic and social conditions that we accept for some people, who we may or may not think have done something to deserve it.

Very similar logic that leads us to punish intentionally also allows us to accept the conditions that serve as de facto punishment.

Those kids can go to that school because, well, they must deserve it.

Those people can live in those conditions because, well, they can handle it.

There is another way.

And it doesn’t necessarily require us to hold hands and all love one another.

You don’t necessarily have to be a “bleeding heart” to be against blind, irrational punishment.

Everywhere you look blind punishment creates new problems and deepens others, it is short sighted and expensive, and it leaves deep scars that are passed on to future generations.

Creating institutions around the blind belief that we must hurt people, often at their most vulnerable moment, only further alienates and marginalizes them from society.

Hurting someone who is already hurt is one of the least effective things you can do if the goal is to change their behavior.

Show me someone who is deeply damaged, disconnected, violent, angry, and alone, and I will show you someone who has had more than their share of punishment brought upon them, both by individuals and institutions.

Hurt people hurt people.

Punished people punish people.

In the battle between compassion and punishment, compassion just flat out works better.

With 2.3 million people incarcerated in jails and prisons, disproportionately people of color, we are spending $80 billion a year to lock people up in a bloated, broken, ineffective system that gets more money for when it fails. Most people who are locked up are eventually released, and over half of those folks come back within three years. It’s not working.

And every year, there are 3.3 million students nationwide, disproportionately black and Latino, who are suspended from school, denying countless hours of precious instructional time to students who need it most. These suspensions aren’t improving schools or changing behavior in positive ways. It’s not working.

That’s not to say that there isn’t a role for some punishment in society, of course there is.

But let’s be smart about it.

Whenever a society brings intentional harm through punishment, it should be proportionate, measured, purposeful, meaningful, evidence-based, and designed to bring about positive results, both individually and collectively.

Above all, we have to get past this idea that punishment and accountability are the same thing. Pushing someone away, sticking them alone in a cell, or at home on a suspension, does not require them to do the hard work of understanding what they’ve done, make up for it, or change their behavior.

Bringing people in, rather than pushing them away, is true accountability. Incapacitation is not itself inherently wrong, but it must be done with purpose, with intentions to rebuild, reintegrate, and protect.

In many ways, this is actually how we already behave with people who are close to us.

It is how we expect our own children to be treated if they have a problem or have done something wrong, with understanding, context, support and treatment.

Address the underlying needs, provide support that is contextual, and expect higher behavioral standards.

It’s good for parenting, and good for society.

Our institutions can and should reflect this principle.

In the San Francisco Unified School District, we’ve challenged the “punish first, ask questions later” mindset, and the results speak for themselves.

By embracing restorative practices, evidence based supportive interventions, and positive behavioral incentives, we’ve seen suspensions and expulsions plummet, increasing class time for the students that need it the most.

And in schools that have lowered rates of punitive school discipline, they have also seen corresponding increases in graduation rates, attendance, and school satisfaction.

And I’m also proud to be a part of the #cut50 movement, where we are working to cut the prison population in half by elevating smart solutions that can reduce incarceration while keeping us safe.

This is not just an idea, it’s already happening:

Dozens of states around the country have moved away from an over-reliance on unnecessary, arbitrary punishment, and towards systems that are intentionally designed to change behavior.

In Georgia, where their Republican Governor has championed criminal justice reform, they’ve created new alternatives that address underlying needs, such as drug courts and mental health courts. As a result, they’ve seen their incarceration rate drop, along with their crime rate.

Arbitrary, irrational punishment isn’t just bad for the people who are punished; it’s bad for all of us. By committing to solutions that are intentional, contextual, individualized, evidence based, and yes, compassionate, we can expect better outcomes for those on the receiving end, and a better society for all of us.

Next time you’re confronted by the “punish first” mentality

Ask why?

What goals will punishment accomplish and how do we know?

You may be surprised the answers you get, or the lack thereof.

And we should also reflect on our own tolerance, or even conscious support, of punishment. More often than not, our support for punishing others says more about us than it does about them.

Punishment is often a way that we attempt to affirm our own value, and at times, relevance, status and safety within a group. And sometimes, it’s simply because someone did it to us.

But just like when it manifests itself in our institutions, it more often than not brings a false, superficial, if temporary, satisfaction. Sometimes we choose punishment because we feel like we are supposed to, but it will rarely fulfill our deeper need for value and belonging.

Punishment doesn’t work for us either.

Real sense of self worth and belonging comes with the harder, more meaningful understanding of our shared connections, and recognition that all of us are much more than one thing we’ve done.

Such understanding doesn’t ultimately come at the expense of others.

We are all complex and flawed.

But for the grace of God, there go I.

Without punishment to fall back on, we’re going to have to learn how to be more purposeful, thoughtful, creative, humble and understanding.

Without punishment for punishment’s sake, we are exposed.

Individually and collectively, we can challenge our addiction to punishment, and demand a world where our own behavior, as well as our collective institutions reflect the best of us&hellip:

Empathy, understanding, compassion, humility.

It’s a little scary, but that’s the kind of world that I want to live in.

Hopefully we all do.

Matt Haney is the President of the San Francisco Unified School District Board of Education and Policy Director for #cut50 and #YesWeCode.

“America has an addiction to punishment.” originally published on Medium.

Responses are closed for this post.