The Power Dynamics of Theatrical Storytelling

Posted on 12 November 2015

Theatremakers need to demand more from the institutions that are teaching their art. I keep finding great big gaping holes in people’s knowledge of storytelling and the dynamics of creating story. Today I have decided to fill a couple holes.

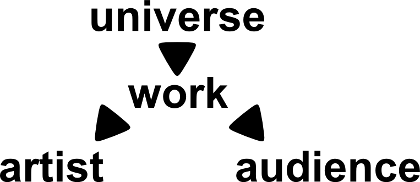

In 1955 Oxford University Press published a book by M.H. Abrams called, The Mirror and the Lamp: romantic theory and the critical tradition. The work largely covers the various movements in literary and art criticism in the eighteenth century. What is most memorable/useful about this book is found in the first few pages of its introduction. Here Abrams outlines the relationships among artist, audience, creative work, and the universe as used by critics. Below is a replication of the graphic the author provides.

Abrams says, “A critic tends to derive from one of these terms (the) principal categories for defining, clarifying, and analysing a work of art, as well as the major criteria by which (the critic) judges its value.” The primary questions critics ask of a work are these:

- How well does this work reflect the nature of the universe?

- Does it truthfully portray human interaction?

- How well does the work represent the artist’s intentions?

- How much insight, creativity, and originality does the artist invest in this work?

- How well does the work communicate to the audience?

- Are they moved emotionally?

- Are they made to think more deeply about the universe in some way?

- Do they find the work memorable?

- Are any morals put forward such that they enlighten the audience?

- Does the response of the audience mean anything in this work’s case?

- Who is doing the responding and why?

- Does the work stand on its own without reference to the artist?

- Does the work stand on its own because of or in spite of its relationship to the universe as we know it?

Different critics will give different weights to these questions, depending upon their particular theory of art.

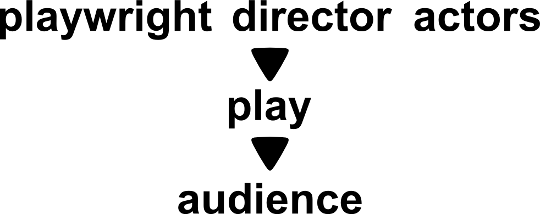

M.H. Abrams is looking at the creation of art as a single person endeavour. These questions are added to the instant a work becomes collaborative. Suddenly, we have to think about who is contributing what and why. In theatre, cinema, and television we have an added structure that could be portrayed in this manner.

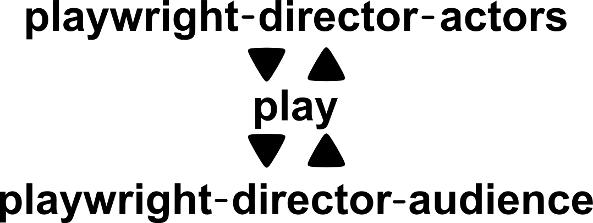

Collectively writers, directors, and actors cooperate to create a play. This play is then presented to an audience. However, I have portrayed a relatively flattened structure. Despite the innovation of democracy, our culture is still enamored with hierarchies and the creating of theatrical art can look like any one of the below structures.

So the question we may want to wrestle with is: what difference does it make shifting who is at the top of the theatrical hierarchy?

Playwright

The playwright is traditionally considered the most crucial element of staged storytelling. People are interested in whether a play was written by William Shakespeare, Antonin Chekov, or Neil Simon. Books on directing theatre at times start with advice on how to break down a script in order to be true to authorial intent. In The Director’s Craft: A Handbook for the Theatre, Katie Michell talks about, “Organising your early responses to the text and building the world that exists before the actions of the play begins.” She then puts forward six preparatory steps a director needs to take before beginning rehearsals including list-making, research, and collating together the biographies for each character.

Basically she is encouraging people to go through a work with a fine-tooth comb in order to put forth a story with insight, integrity, and professionalism. When this is done out of respect for a work, the results can show a certain maturity of performance. Where things go awry, such that we start hearing the term “tyranny of the author” thrown around, is when a playwright starts making absolute or unreasonable demands of the production.

Neil Simon insists that his plays are staged precisely as indicated in his script. He and others also insist that the words are spoken as written, otherwise you have broken contract for their use. Some plays have an expensive price tag, with companies expected to buy individual copies of the script for each of their players. This pushes out of the market small and community theatre companies.

Basically this hierarchy is one where all vision is invested in the writer, the director’s role is solely interpretation, the actor’s role is to fulfill the vision, and the audience is supposed to absorb the vision.

Director

In cinema the director’s role is often seen as the most crucial. We see films because they were directed by George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, the Coen brothers, etc. Theatre gets a little of this with people like Baz Luhrmann.

In this case the director has the vision, the playwright is commissioned in some sense for scenarios, the actors fulfill the vision, and the audience is expected to absorb the vision.

Shakespeare is frequently reinterpreted in order to convey the vision of a director and make the work more accessible/relevant to audiences today. Baz Luhrmann’s interpretation of Romeo and Juliet, where the Montagues and the Capulets are running around with guns, is one example.

Directors are in a better position to manage spectacle than either writers or actors. Spectacle brings in more money than art. This is one reason why Hollywood focuses more on its directors, in order to cover their bottom-line. They can also potentially be the best go-between for actors and playwright, helping to birth a play.

Actor

Charismatic actors and actors who have performed well-loved roles can have popular appeal and thereby a certain amount of power in the production of a play. In law there is an aphorism that goes, “A man who is his own lawyer has a fool for a client.” The same can be true for actors who write for themselves. This is not always the case, the trick is in how well actors can ensure the work is about presenting an engaging story to the audience and not about inflating their public status.

Some actors get around this by either collaborating with or commissioning a writer. This puts the playwright in a more powerful position than the director. Those who have succeeded in wearing both hats have largely done so through one person shows such as Looking Through a Glass Onion by John Waters or Gestation by Deb Margolin.

More than a director really, actors are always co-storytellers with the playwright. Their bodies and their voices are new layers of story which bring truth, reality, even beauty to a play. To do this they must remain focused on the work as a whole, their interactions with others, and take pleasure in the collective success of their troupe.

Audience

Having the audience at the top of a hierarchy sounds almost democratic. The problem is: who is the audience for any particular play? Is the production a snake oil pitch, and therefore plays as much if not more to the advertiser than the public. Is the work meant to please those in power, such as a dictator, while spreading propaganda to the masses. Of course if you simply have a theatre focused solely on turning a profit, then what plays are chosen becomes a conservative exercise in what is least offensive, most spectacular, and therefore most broadly appealing to the audience.

Audience control works best in improvised theatre. That structure seems relatively flat. You only have actors, audience, and a play. But that is a seriously over-simplified way of looking at what is happening. The actors spend hundreds of hours practising how to be collaborating playwrights and directors in the moment while acting. Playwrights and directors haven’t been removed: they have been internalised and some of their responsibilities are given to the audience, as below.

Improvisational theatre can sometimes struggle or lose its appeal after awhile, because it often relies on cliches and the stories may not achieve intellectual complexity or emotional depth. That’s why skilled and dedicated playwrights are so useful.

In some ways the audience is always the most powerful part of theatre. Works are created to be seen and heard. If they aren’t then playwrights and directors alter their approaches until they finally open a dialogue with the public. The question is how much of the public do you wish to appeal to? To which part of the public do you wish to speak and why?

The real artistry of creating theatre happens when people are focused on presenting a good story well. Everyone needs to respect everyone else’s roles, because only then are they likely to express their skills to the fullest. I love it when cast and crew surprise me with thoughts and ideas of which I could not conceive until they added them to the mix. The show is always the better for it. The main issue is for people to learn the humility of dedication to their art, such that egos are set aside and everyone is willing to listen and to cooperate. That’s when the magic happens.

In peace and friendship,

Katherine

Abrams, M.H. (1953) The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition.

London: Oxford University Press. p. 6.

Mitchell, Katie (2009) The Director’s Craft: A Handbook for the Theatre.

London: Routledge. p. 11.

Responses are closed for this post.